The Whole Haunted World #1

Halloween's Bad Rep, News from the Beyond, and Part I of The Skeptic's Guide to Ghost-Hunting

Welcome to the first (free!) issue of my new paranormal/Halloween-themed newsletter The Whole Haunted World! After this debut, this will be a paid subscription (although don’t worry - my author newsletter Every Day is Halloween will stay just the same and always be free).

Why am I asking you to cough up dough for this one? Here’s the deal: The Whole Haunted World is going to give you original full-length essays (or articles, or features, or whatever you want to call them) that you won’t get anywhere else. These will be the same kind of detailed, researched, thought-provoking work that has garnered my books like Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween, Ghosts: A Haunted History, Calling the Spirits: A History of Seances and The Art of the Zombie Movie acclaim and awards (confession: if you’ve read my work before, you know that I lean into the skeptical side although I find everything to do with the paranormal fascinating). Each issue will also include some news from the world of spooky happenings, maybe a bit of appropriate fiction, and some cool images…plus, I’ll be serializing a complete book, The Skeptic’s Guide to Ghost-Hunting! I’ll also turn one article every month into a podcast, for those of you who prefer to listen. You’ll get two issues delivered to your inbox or Substack app every month, with the occasional surprise extra.

I also hope to make this a little community for those of us are endlessly fascinated by all things haunted. I’d love to hear your thoughts! Tell me what you’d like to see more of (or less). Maybe I’ll even host a live chat or two. Substack offers many possibilities for the exchange of ideas, and I look forward to digging into those with you.

Thank you for your support and interest, and now let’s dive in!

Happy Halloween - Lisa

News from the Beyond

Fun tidbits from around the world…

This New York Times article on Halloween is one of the best I’ve ever read (and that’s not just because I’m quoted throughout!)

CBS Chicago is taking us on a tour of the town’s haunted Hooters (and feel free to argue that all Hooters have an abundance of ectoplasm already)

The Moray Playhouse in Scotland seems to think it’s unusual to have a haunted theater

West Virginia officially has a Paranormal Trail complete with a downloadable digital passport

If you’re in the Salt Lake City area, you should check out a performance of “Paranormal Percussion” and report back here

CBS News Minnesota profiled the investigators behind the new webseries Midwest Paranormal

Canada has a new paranormal series in Repossessed, now streaming on History and StackTV

Shameless self-promotion: I had a great time taping four episodes of this fun PBS SoCal webseries Won’t You Be My Gamer? Episode 1 (now streaming) and 2 cover Halloween games; in 3 and 4, we dig into ghost games.

The Devil’s Birthday: How Halloween Got Its Bad Rep

(Portions of this work previously appeared in Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween)

If you’re shopping for a book on Halloween history, you might think a low-priced paperback called The Facts on Halloween looks like the ticket. If you pick up a copy of that book, though, and glance at the rear cover (or read more carefully through the online description) you might notice something like this: “Trick or treat? Every Halloween children set out to gather as many goodies as they possibly can, acting out practices they know little about.” If your inner alarm bells are starting to jangle at that, wait until you get into the meat of the book between the covers and read passages like this description of ancient Celtic tribes: “They apparently believed that on October 31, the night before their New Year and the last day of the old year, the Lord of Death gathered the souls of the evil dead who had been condemned to enter the bodies of animals.” Despite the admittedly delicious Sam Raimi reference, that’s some pretty seriously whack stuff: the Celts did not worship a “Lord of Death,” and there’s no evidence to support the notion that they believed dead souls entered animal bodies. The Facts of Halloween goes on in similar fashion from there.

Forgetting the irony of the book’s title (the book is definitely not heavy on the “facts”), this massively incorrect portrayal of the Celts begs the question: where did this nonsense come from? Did the authors of The Facts on Halloween (John Ankerberg and John Weldon), or the authors of any number of similar Christian readings of Halloween, all gather at some conference to generate an accepted alternate history?

No, they didn’t need a conference because they had something better: a single, definitive work, written by a Celtic scholar whose works appear in libraries all over the world. Yes, in this case we can trace Halloween’s bad rep as “the Devil’s Birthday,” “Helloween,” or “a celebration of the Lord of Death” to a single point in history.

That point is a man named Charles Vallancey.

Before we get to Vallancey, though, let’s look at the actual historical beginnings of Halloween. First off, the Celts were a mash-up of tribes once spread across Europe and the British Isles. The Druids were a caste within Celtic society who kept the law and oversaw religious rituals; they also passed down the tribal histories orally, leaving nothing written behind. Although we have enough archaeological evidence to know that the Celts were skilled at things like metal-working and road-making (and that they likely did offer human sacrifice), what we otherwise know of them comes from Roman or Catholic sources, either soldiers (like Julius Caesar) or monks who encountered them. Caesar, whose accounts of the Celts (found in his Commentaries on the Gallic War) is likely colored by his own imperialism, described the Celts as fashioning “huge images of the gods…which are woven from wicker,” and filling them with living prisoners before setting them on fire. The Greek philosopher Strabo notes that among the Celts, “witlessness and boastfulness is much in evidence.” These hardly seem like traits that would have allowed the Celts to battle effectively against Roman incursions for centuries.

By the 6th century A.D., Celtic tribes were facing a far more effective opponent, though: Catholic missionaries. Moving into Ireland, these early missionaries (including St. Patrick) learned the Celtic tongue and began to record the histories and stories that the Celts themselves hadn’t. They wrote of great heroes like Cú Chulainn and Fionn mac Cumhaill, the epic battles between the virtuous Tuatha Dé Danann and the evil Fomorions, and the four great Celtic quarter days: Imbolc, Beltaine, Lughnasadh, and Samhain, with the latter marking the end of the year (each of these days took place exactly between a solstice and an equinox; dates shifted later as the Catholic Pope Gregory replaced the old Julian calendar).

Samhain, which translates literally to “summer’s end,” was mentioned frequently in the Celtic texts, as both an administrative time (debts and taxes were collected) and a massive feast (since livestock had been brought in from the fields in preparation for the cold Irish winter). As a line between years, Samhain was a liminal time when the borders between worlds were also at their thinnest, and so the Celts filled their feasts with ghost stories, like that of the courageous warrior Nera who follows a band of malicious sidh (think demonic fairies) through a portal on Samhain night and is trapped in the Otherworld, where time passes at a different rate.

When the Catholic missionaries came to Ireland, the Church practiced the doctrine of syncretism, which meant that they attempted to co-opt existing pagan religious observances rather than stamp them out; slapping Christian meaning onto old festivals and temples had proven far more effective than trying to force Christianity on potential new converts. Although there is some debate over the establishment of November 1st for All Saints Day (that happened in the mid-eighth-century) – some scholars believe it was done to feed the influx of pilgrims coming to Rome since harvest had just been completed – it seems likely that it was selected to co-opt the Celtic Samhain. There are also Halloween experts, by the way, who believe that the holiday derives entirely from the Catholic side, but personally I fall squarely into the Samhain camp; I don’t see anything particularly macabre about honoring a bunch of saints (despite the fact that there are some pretty horrific stories about those guys). I think Halloween unquestionably gets its spooky side from those Celts.

Having admitted that much, let’s get back to this modern Christian assertion that Halloween goes beyond merely macabre to downright Satanic, based on an ancient Celtic worship of a Lord of Death. How did we get from a Celtic new year’s party to an orgy of death?

Back to Charles Vallancey…

Charles Vallancey (1731-1812) was a British military engineer who is described in the Dictionary of Irish Biography as a “soldier and antiquary.” He was first sent to Ireland sometime after 1750, and in 1761 or 1762, he was given the rank of major of engineers and assigned to oversee an Irish surveying mission. Vallancey, however, was no ordinary engineer; he was extraordinarily well-read in history and linguistics, corresponded with many of the leading proponents of then-fashionable Orientalism, and fancied himself a scholar and writer. He also had a succession of four wives and a dozen children, meaning that he was also constantly in need of money, so he took on work (alongside his engineering and military duties) like translating. He soon developed an obsession with the lore and language of Ireland’s ancient Celts, and he wrote hundreds of pages of collected fact, observation, and speculation on the green isle’s early inhabitants.

There was just one problem: Much of what Vallancey recorded was wrong. Not just slightly wrong, and not just a simple error, but knowingly, hugely, wrong.

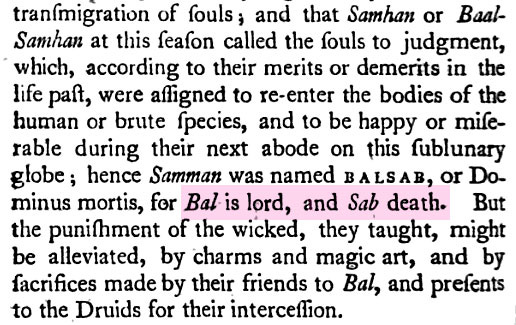

By 1786, when Vallancey published the third volume of his opus Collectanea de rebus Hibernicis, it was already well-established that Samhain meant “summer’s end,” but Vallancey was out to create his own connections, and through a series of arguments that are, at best, difficult to follow, he concluded that this was a ‘false derivation’, and then went on to state that Samhain was actually a Celtic deity who was also known as ‘BALSAB … for Bal is lord, and Sab death’.

It doesn’t much matter that the name ‘Balsab’ appears nowhere else in Celtic lore, or even that Vallancey’s work was dismissed during his lifetime (the esteemed historian Sir William Jones said of Vallancey, “Do you wish to laugh? Skim the book over. Do you wish to sleep? Read it regularly.”). Collectanea de rebus Hibernicis ended up comprising six volumes, and became a standard accepted work on Celtic history and lore, finding its way onto library shelves all over the world. Vallancey’s work thus formed the strange alternate history of Samhain (and its descendent Halloween), running alongside the traditional Celtic folklore texts and Irish dictionaries that defined the word and the history correctly.

How is it possible that religious and community leaders would be applying the writings of a romantic who was denounced in 1818 as having written “more nonsense than any man of his time” (according to an 1818 issue of the London Quarterly Review) in order to in turn denounce a major holiday?

To answer that, we need to look at how Halloween advanced in the 20th-century. By 1900, folklore texts proliferated and many discussed Halloween (or, as it was then printed, Hallowe’en – the apostrophe would remain in place until the 1940s), but the first full-length history of the holiday wouldn’t be published until 1919, when an American librarian named Ruth Edna Kelley produced The Book of Hallowe’en.

Surprisingly, Kelley’s book remains more accurate than much of what came after. Perhaps her library didn’t stock Vallancey’s work, or maybe she was discerning enough to realize it was just plain wrong. In either case, she stuck to the correct definition of Samhain.

It would be another 31 years before the next major study of Halloween’s history: Halloween Through Twenty Centuries, by Ralph and Adelin Linton, was part of a series called “Great Religious Festivals.” Despite the changes that had taken place in the holiday during the decades since Kelley’s book – trick or treat had become a significant part of October 31st, for example – the book is shorter than Kelley’s…and far less accurate. Take this strange sentence, the third in the entire book: “At the same time, it commemorates beings and rites with which the church has always been at war.” On the next page we read, “The earliest Halloween celebrations were held by the Druids in honor of Samhain, Lord of the Dead, whose festival fell on November 1…The rites performed on this day were eerie enough to thrill the most blasé, but the spirit of fun was sadly lacking.” The history becomes even more confused after that, claiming that Samhain was a “joint festival” celebrating both the Lord of the Dead and the Sun, and that much of Halloween was based on “an exceedingly ancient, even pre-Celtic, cult of the dead.” The last page of the book concludes, “Halloween has now become what the sociologists refer to as a degenerate holiday.”

The next major history of Halloween, Lesley Bannatyne’s Halloween: An American Holiday, an American History, would appear in 1990 and be the best, most factual book on the holiday published up to that time, but by then it was too late: Halloween Through Twenty Centuries stood for forty years as the most recent and definitive study of the holiday, and its mistakes (which are legion) were firmly in place. Christian groups throughout America were urging parents to keep their children from celebrating a holiday during which (according to a 1993 issue of the journal Orthodox Life), “human beings were burned as an offering in order to appease and cajole Samhain, the lord of Death.” In the 1970s, evangelical leader Jerry Falwell first created the idea of a “Hell House,” a Christian answer to the increasingly popular haunted houses put on by non-profit groups like the Jaycees and Campus Life throughout America (haunted attractions wouldn’t become big for-profit enterprises until about twenty years later).

Hell Houses soon became both major propaganda and major money-makers for churches, meaning it made good business sense to follow Vallancey’s (and the Lintons’) lead and label Halloween as a Satanic festival (which became even easier during the height of “Satanic panic” in the 1980s).

So, the next time you encounter someone who condemns Halloween as a celebration of evil, you can tell them that they’re following the mistakes made by a single man over two centuries ago. Or perhaps you could talk about the psychological benefits of a holiday that has, over the last thirty years, morphed into a chance to test our fears in playful, safe environments.

Or you could stay silent, don your devil costume on Halloween night, and pretend Vallancey was actually right all along.

The Skeptic’s Guide to Ghost-Hunting

(This is the first installment of my complete serialized book The Skeptic’s Guide to Ghost-Hunting; subscribers will receive a new section each month. Enjoy!)

Chapter One (Part One)

On a cold, windy night in September of 2014, I found myself in the balcony of the concert hall at the Stanley Hotel in Estes Park, Colorado. Situated high in the Rockies about 90 minutes from Denver, this historic hotel was built in the first decade of the 20th century by F. O. Stanley, the wealthy inventor (with his brother Francis) of a line of steam-powered automobiles; F. O. suffered from tuberculosis and had been prescribed fresh air, so he headed to Colorado. Stanley’s health improved, and he and his wife Flora fell in love with the area so he built his own home resort there.

The Stanley failed to turn much of a profit until, decades after Stanley’s passing in 1940, it fully embraced its paranormal side. That started in 1974 when Stephen King and his wife Tabitha famously stayed in Room 217, where the author encountered something that inspired him to write The Shining. After the 1997 mini-series adaptation of the classic haunted house novel was shot at the Stanley and aired, more and more horror fans made the hotel a travel destination, and some of those fans (as well as the hotel’s staff) reported that the hotel was actually haunted…as in, very haunted. The Stanley, which has been called “a Disneyland for ghosts,” is thought to be one of the most haunted locations in the world.

In 2014, I was there for a writing retreat but I booked a spot in an overnight paranormal investigation. At the time I was knee-deep in writing my book Ghosts: A Haunted History (published in 2015), at about the halfway point. I was looking forward to a stay in the Stanley for both relaxation and research; the paranormal investigation wasn’t my first, but it would provide both inspiration just at the time I needed it and an opportunity for great photos I could use in the book.

Before I started work on Ghosts, I was a full-on, hard-core skeptic, one of those who eagerly devoured every issue of The Skeptical Inquirer, smirking at all the stories about gullible believers. When friends had told me they’d encountered ghosts, I’d flat-out told them they’d seen shadows or imagined the whole thing. I’d participated in one weekend-long investigation of a very haunted venue in Northern California, but encountered nothing weirder than some mag flashlights that rolled on their own (which I suspected they’d also do in a non-haunted venue) and some EVPs that just sounded like static to me. I’d never had anything even close to a paranormal occurrence, and my life philosophy didn’t allow for the possibility of the dead returning as spirits.

But – as I’ve now stated in any number of media interviews – one can’t write a global, historical study of ghosts and maintain that level of skepticism. Belief in ghosts is simply too prevalent. It’s found in all cultures around the world and throughout the ages; in times and places where religion denies the existence of ghosts (believing that souls cannot return after death), teachings still explain ghosts by suggesting that they are demons or tricksters tempting grieving humans. When it comes to the supernatural, belief in ghosts is second only to belief in gods, and sometimes the two go hand in hand: in classical Greece, seekers of spirits could ask Apollo’s Delphic oracle for instructions, and in our modern times particularly frightening entities might be exorcised by Catholic priests.

While there is no concrete, inarguable evidence to support the existence of ghosts (although certain items, like Captain Hubert C. Provand’s 1936 photograph purported to show the “Brown Lady of Raynham Hall,” are still argued over), millions of witnesses over the centuries have reported everything from sensing the presence of someone who is not there to seeing full-body apparitions. To my mind, it makes no logical sense to assume that all these people have been deluded, frauds, attention-seekers, or mentally ill.

Something else is going on.

(Chapter One of The Skeptic’s Guide to Ghost-Hunting will continue in Issue #3 of The Whole Haunted World)

SPECIAL DEAL

Right now the University of Chicago Press is offering a great deal on selected spooky books, including three by me (Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween, Ghosts: A Haunted History and Calling the Spirits: A History of Seances). Use code HALLOWEEN30 at checkout for 30% off (hey, that’s a way better deal than Amazon!).

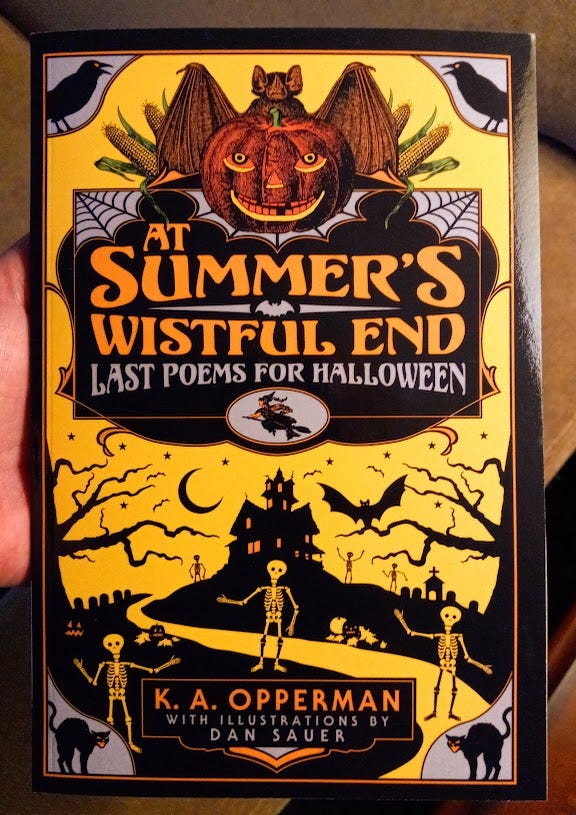

CELEBRATING WITH A GIVEAWAY

My friends at Jackanapes Press were kind enough to provide me with a copy of K. A. Opperman’s gorgeous new book of Halloween poetry, At Summer’s Wistful End. If you haven’t read Kyle’s work before, I love it and consider his verse to be quintessential Halloween reading!

If you’d a chance to win this copy, leave a comment before October 23 (so you’ll have the book hopefully in time for Halloween!) and I’ll randomly choose a lucky winner to send this to. Sorry, this is only open to U.S. residents.

COMING NEXT ISSUE…

“B340: How the Queen Mary (and Disney) Created a (Real) Haunting,” a review of the Queen Mary’s “Grey Ghost Project,” and a brand new Spine Tingler short story set aboard the QM!

Thanks for reading this far! If you’ve enjoyed these little trips into Halloween and paranormal history, I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber. For $5 a month (or $50 annually), you’ll get original, exclusive content like this delivered to your inbox twice a month, and you’ll be part of a community who share your interest in all things spooky.

🎃 🎃 🎃

Great article! Regarding spooky hotels, I once stayed at the old Hotel Colorado one night in Glenwood Springs, CO, that has been around since 1893 and hosted Teddy Roosevelt in 1905 when he went bear hunting. Noting the hotel had been around a while, I asked the desk clerk if there were any ghosts. She said there were many stories, but didn't elaborate.

There are long eerie hallways as at the Stanley, and I was wondering if I would see anything waiting for me at the end of one. I didn't, but much later in the night I was awakened when I felt a push on my ankle. I suppose it was their way of letting me know the hotel was indeed haunted. I definitely recommend a visit to this old and stately hotel just for the atmospherics if nothing else.